Five Phases Of Effective Reliability Within Organizations

Reliability is important to everybody in a business. There’s a common misconception that it’s just important to engineers. We must change this mindset and think of reliability as a team sport that everyone needs to be part of.

As an organization, there are five key phases to implementing effective reliability across teams. The five phases of organizational reliability are:

- Implementing SLOs

- Calculating error budgets

- Eliminating toil

- Defining SLAs

- Defining SLIs

1. Implementing SLOs

The first phase of building reliability is implementing service level objectives (SLOs) because availability and performance are crucial aspects to monitor.

Service level indicators (SLIs) and SLOs play a significant role in reliability as they encourage teams to think like users. Once developers and engineers start to think like users they start to ask different types of questions. SLOs help accomplish this because they provide a tool for measuring and validating service health.

SLOs are designed based on a user’s point of view and the factors that matter most to them. They will also factor in your business requirements.

The services and products that you’re building may have tens of hundreds of features but what are the core features that the users are using day in day out? What are the most important features for your product to be successful and for you to provide a positive user experience?

SLOs are essential because they reflect a user journey and make customer happiness a metric, therefore, that’s a priority. If customers are unhappy, they’re not going to come back and use the product, so creating SLOs that reflect what users want give development teams a road map to follow.

Once we get in the mindset of a user, we start to think about how useful the features we build are to the user and if it has been implemented in the most simplistic fashion. It shows a better understanding of when to increase development velocity and when to focus on improvements.

Product managers always want the latest feature and it can be very difficult for engineers to get improvements prioritised. With service level objectives you can show with data that your SLO is decreasing and you need to work on stability and focus on improvements. Conversations become much easier when you’re not just making requests in sprint planning or on a one-off meeting with no data.

When building SLIs, you need to look at how your customers are using your services. This is why understanding user journeys and considering what are the most important and essential flows through your system are so important.

SLOs need to be set at the customer’s pain point - what can cause the customer the most pain whilst using the product or this specific feature of that product?

You also need to ensure that SLOs are monitorable - if you can’t monitor them then you will have no way of knowing whether you are succeeding or failing that objective. Ensuring you get the data you need to make sure you can keep the SLOs up to date is critical.

Reviewing and revising SLOs over time as your services change and grow and you implement new features is critical. What becomes important to customers changes too and teams need to set a schedule to review the SLOs that were previously set and make sure they still reflect customers’ happiness. If they don’t, you have SLOs against things that may not be important anymore.

2. Calculating Error Budgets

Error budgets are another phase of implementing reliability that can improve reliability. Error budgets can be set between teams and refer to the number of errors that can accumulate within a service or product before customers get upset.

Errors can be caused by various issues within the product - availability, performance downtime, and scalability issues to name a few.

There are a number of factors that can cause errors to happen; it’s not just the application itself. It’s up to teams to first identify what they’re trying to measure, therefore, every error budget will vary.

Error budgets are calculated using the service level indicator (SLI) equation.

SLI = [Total good events / Total events] x 100

The percentage that comes from this equation is referred to as the SLI and each one is assigned an objective. The remainder of what’s left is deemed your error budget.

Error budgets serve many vital purposes. On the surface, they’re essentially metrics to understand how products or services are running but when you look deeper it’s actually more than that.

For example, if the budget is close to being exhausted you may trigger policies to prevent it from running out. This could include things like code freezes where new updates are allowed to be implemented (only improvements) or you may go back to a previous version because it was more stable than the one that you’ve just rolled out.

It also provides you some breathing room as you’re able to tell when an incident won’t jeopardize the error budget and you don’t panic as much.

What Do You Do If You’re Close To Or Spent Your Error Budget?

If error budgets aren’t spent, it gives development teams leeway to innovate and take more risks such as launching new features and improvements for customers.

If it’s trending towards being breached then developers and engineers need to be focused on reliability and improving the performance of a single microservice or a set of microservices that provide a feature.

An error budget is the amount of acceptable unreliability a service can have before the customer’s happiness is impacted. If the service is well within the budget then developers can take risks, if they’re trending towards their budget then they can take fewer risks.

Error budgets normalize failure as a part of the development process. It allows us to make mistakes without getting caught by our customers.

You’re never going to be able to implement everything perfectly 100% of the time but what this enables you to be able to do is determine when you have implemented a problem and take time out of the normal development cycle to implement improvements to make it more reliable.The error budget provides reliable data to development teams on how to set release velocity.

Spending An Error Budget

A very common misconception is that error budgets are consumed in one continuous chunk with a single incident but that’s not always the case.

There are many scenarios or incidents that can happen where the error budget is actually consumed in small portions throughout a week, a month, or a year and that’s perfectly acceptable.

From a financial services perspective, if you have a payment service that has a service level agreement of 98%, we know that a service level objective needs to be higher than a service level agreement. You’re going to need to set the service level objective to 99% availability so the error budget in this context is one percent.

That’s the difference between the SLO and the SLA. For example, if one percent is in a 28-day window that’s a normal month - that gives you about 3.5 days of downtime. Now let’s assume that after 15 days, the SLI is 99.5%, you’re meeting your SLO and you’re within the error budget. If the service level indicator drops below 99 percent then you’ve used your budget and you’re no longer meeting your SLO. If that happens then you need to take some corrective action.

Fives Nines

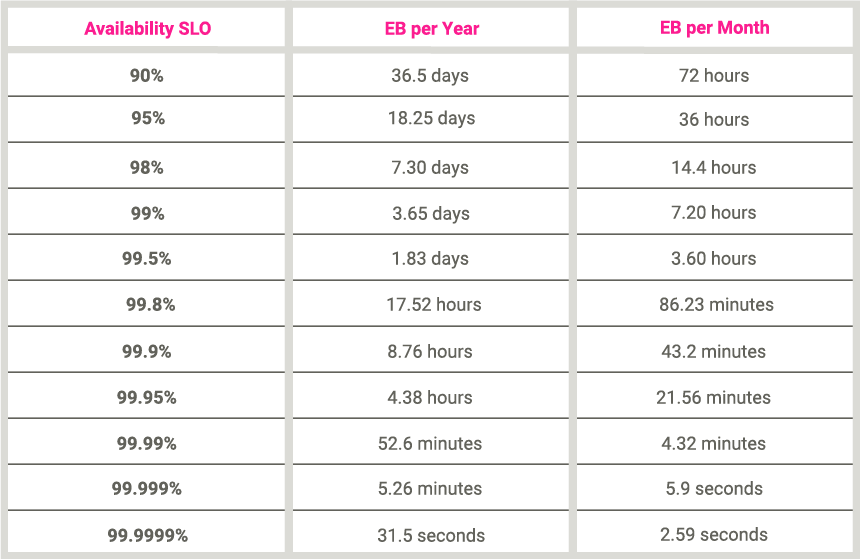

This is a table that can be used to reflect on SLOs. The common conception is that everyone wants to achieve five-nines of availability.

Five nines being the second from the bottom so that gives you an error budget per year of five minutes and an error budget per month of just under six seconds. You have to question whether that is possible in the services, applications, and products that you’re providing.

There is also another misconception that setting the SLO has to be more strict than the underlying infrastructure that your application runs on. You can’t get any more reliable than the infrastructure that you’re currently running on because that’s the lowest common denominator. If the infrastructure that you’re running on only provides you with four nines of uptime or availability then you can’t possibly have an SLO for your application of five nines - it’s just not going to be realistic because the infrastructure is going to win out at that point.

An error budget is reliability versus pace of innovation. That’s the question that we’re asking ourselves: which one of these can we push more?

Innovation means change and the main reason behind instability is change. The development toil for new features is always competing with the developer toil required for stability. Change is inevitable and therefore the error budget works as a control mechanism to ensure that we set attention when stability is being degraded.

How Can Developers Spend Their Overall Budget?

An error budget is like having a budget that you’ve been given by your parents. For example, they’ve given you a hundred pounds - you can go and spend it whenever and whatever you want. It’s an allowed expense. ‘Allowed expense’ means unreliability. You’re allowed to spend your error budget within a given period as long as you don’t overspend it so you can’t go over your limit. Developers can spend the error budget any way they see fit.

They can spend it providing new features working on new functionality but as the team advances in maturity and gains better control over how to spend their budget, they begin to strategically spend their budget by taking more calculated risks and shipping experimental features.

What To Do When You Are Close Or Spend Your Error Budget?

Firstly you need some way of being able to alert on this, typically 50%, 75%, 90%, and 100% as an example. If you’re trending towards those top-level percentages then you need to make a decision - that could be rolling back to the previous version that was more stable or that could be stopping shipping new features and working on making the current version of the product more stable.

3. Eliminating Toil

Eliminating toil is about reducing the number of repetitive tasks that a team has to do. By eliminating toil you’ll free up energy and time to perform other tasks.

Reducing toil also increases morale and allows teams to focus on what they would deem to be more interesting work.

You can eliminate toil in many different ways, for example writing guides or processes for tasks or documenting specific flows through the system so that new joiners can read documentation to get up to speed quickly and start adding value.

The most effective way to implement this principle is to:

- Create standards and templates

- Make guidelines

- Invest in tools that to automate manual tasks

- Look for areas of high toil

- Prioritize improvements

- Include toil elimination in sprints

- Plan time for regular improvements

Eliminating toil and making improvements will make everybody’s life better in the future.

4. Defining SLAs

Service level agreements (SLAs) are a type of key performance metric that can be monitored by outside observers without having to have internal monitoring data. This allows stakeholders to verify for themselves that the SLA is being met.

For example, you could have an SLA that says your service will be online 99.99% of the time, there’s no nuance or debate to that metric the service is either online or it’s offline.

SLOs help ensure that your service level agreements (SLAs) aren’t breached. They allow you to keep them in a safe space away from any legal trouble. As a result, SLOs should always be made stricter than the corresponding SLAs and that gives us that buffer room.

SLA is a legally binding agreement between an organization and its customers or end-users. It guarantees that the service will meet certain agreed-upon reliability standards. These standards are usually built on simple objectives and strictly defined metrics.

A good SLA will be ambiguous as it needs to be legally binding while still considering all stakeholder’s needs and factors. Also because it’s legally binding there’s this legal strictness to it whereby it’s unlikely to change a lot because it’s going to take a lot of time to change and also a lot of effort

5. Defining SLIs

A service level indicator (SLI) is a metric that defines the health of a service over time and is used to determine whether the service level objectives are being met.

Setting the right SLI is about understanding what the user expects from a service. You’ve got to get inside the user’s head and think about what kind of service or experience users want from this product and then look at how you can track where that starts to increase or decline.

You don’t want to use every metric that you have available to you in a monitoring system to work out what your SLI is. Choosing too many SLIs can make it difficult to pay attention to the right metric. You’re going to get burdened with lots of noise and it will be difficult to choose which one you should be listening to.

An SLI is worked out by the total number of good events divided by the total number of events wholesale times 100 and that gives you a percentage.

For example, an SLI might be the number of successful HTTP requests divided by the total number of HTTP requests that your service has inbound or the number of HTTP requests that have been completed successfully in sub 100 milliseconds against all of the total inbound requests.

There are many different variations to this. A way of being able to diagnose or indicate whether your services are healthy and providing good customer satisfaction when it’s not is going to be critical for you to get ahead of your user.

What you want to avoid is having the user tell you that the service is being degraded. We need to know that the service is being degraded and act on it. We want to shift ourselves into being proactive. If you’re in the reactive category, the customer is nine times out of ten going to have a bad user experience.