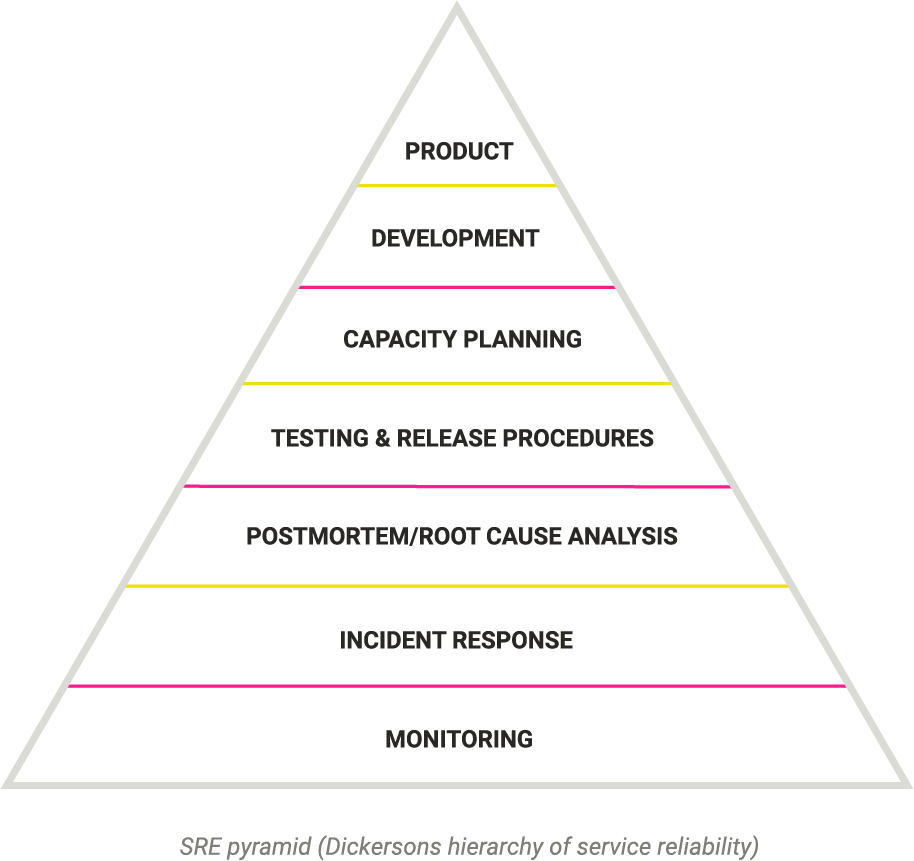

SRE Pyramid: Dickerson's Hierarchy Of Service Reliability

A Site Reliability Engineering (SRE) pyramid, also known as the ‘Dickerson pyramid,’ provides a set of principles that an organization can use to define and improve reliability to promote engineering excellence.

The SRE pyramid borrows heavily from Maslow’s hierarchy of needs – a psychological theory that suggests that our actions are motivated by certain physiological needs.

The idea behind the SRE pyramid is that we can categorize the health of a service in a similar way to how Abraham Maslow categorized human needs. The most basic elements required by a service are at the bottom of the pyramid, and the elements get more advanced as we move further up the pyramid.

Each level is not exclusively dependent on the level below it. But when each level is fulfilled, the levels above it can benefit.

Who is Mikey Dickerson?

The SRE pyramid was created by Mikey Dickerson, a former Site Reliability Manager at Google.

Dickerson created the SRE pyramid in 2013 after leaving Google to work with the United States government to help with the launch of healthcare.gov. His job was to minimize the frequency and impact of failures that could ultimately impact the overall reliability of an application.

Reliability is a challenge for developers, and Dickerson quickly realized that he needed a way to explain Google’s method of increasing site reliability to outsiders. He decided to borrow from the structure of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to create the SRE pyramid which would explain reliability in a simple context.

Why is the SRE pyramid important?

The key idea behind the SRE pyramid is relatively simple. It suggests that to improve reliability, you must first find a way to measure it.

The SRE pyramid provides a clear way for organizations to define what ‘reliability’ means, and to define what will happen if standards are not met. It can prioritize the work to be done before a team is even formed, to help organizations to increase their reliability.

Who can benefit from the Hierarchy of Reliability?

Reliability is a requirement across virtually every industry. Retrospectively trying to resolve problems often requires significantly more resources than preventing a problem in the first place. This can lead to businesses losing time, money, and the reputation they may have spent years building up.

The Hierarchy of Reliability is particularly relevant to engineering – in particular, it is designed to help site reliability engineers to do their job. It can be used differently depending on whether an organization is creating a new team or migrating an existing team.

The overall purpose of the Hierarchy of Reliability is to ensure that the most basic elements of system reliability are covered before moving onto more complex elements. Each failure should be treated as a failure in the reliability of the system.

Dickerson’s 7 Principles Of Service Reliability

The seven key principles of service reliability are:

- Monitoring

- Incident response

- Postmortems and root cause analysis

- Testing

- Capacity planning

- Development

- Product.

1. Monitoring

Monitoring is at the very base of the pyramid because it is the most basic requirement for a functioning system. Without monitoring, none of the other layers of the pyramid can be completely fulfilled.

While it is entirely possible to have a product without monitoring, there would be no way to tell if your customers all got redirected to an error page whenever they tried to access your website. This is a huge problem, given that studies have shown that 73.72% of people who reach a 404 error page will leave your website and not return.

As a result, monitoring should be built into every feature as a basic requirement. It informs organizations whether the system is even working, and means that they can become aware of potential issues before users notice them. This will help avoid them spiraling into a bigger problem which can cause the overall user experience to suffer.

2. Incident Response

An effective incident response protocol ensures that you can successfully deal with a problem if you find one during the monitoring phase. Incident response can be difficult.

Without a proper procedure in place, it can feel tempting to respond immediately without putting in enough thought, in an attempt to deal with the problem as quickly as possible.

In some cases, ‘dealing with a problem’ might simply mean fixing it, but this won’t necessarily be the case. Depending on the complexity of the problem, it could involve temporarily disabling certain features, or redirecting traffic to a different part of the service that is still working effectively.

3. Postmortems & Root Cause Analysis

Postmortems and root cause analysis are both critical when it comes to identifying the root cause of a failure so that it can be avoided in the future. The goal of this is to prevent the same mistakes from happening over and over again by thoroughly addressing the problem and taking the appropriate corrective action the first time it happens.

A successful postmortem involves avoiding blame and keeping things as constructive as possible. Collaboration should be encouraged, and team members should be visibly rewarded for doing the right thing.

4. Testing

Once you have an understanding of what is going wrong, you should attempt to prevent it from happening again in the future. Unfortunately, many organizations end up skimping on this step due to team constraints.

Testing software before releasing it is vital when it comes to reducing the number of errors present.

There are two main categories of software testing:

- Traditional tests

- Production tests

Unit tests are the simplest form of traditional testing, followed by integration tests in which these units are assembled into larger components, followed by large-scale system tests. Production tests are designed to interact with a live production system.

While passing a set of tests doesn’t necessarily prove that software is reliable, failure to pass tests can prove that the software is not reliable.

5. Capacity Planning

Capacity planning enables an organization to meet the changing demands for its products by allocating the correct resources.

The average cycle can be approximated as follows: collect demand forecasts, devise and build allocation plans, review and sign off the plan, and then deploy and configure resources.

Capacity planning should be considered as a continuous, never-ending cycle due to changing assumptions, slipping deployments, and changing budgets within organizations.

6. Development

Before development begins, it is important to do some research to make sure the product that you are creating doesn’t already exist. After doing some research, you can often find that an off-the-shelf product that meets your requirements already exists.

Ensuring that you are solving a problem that will be widely impactful, instead of focusing on fixing a pet peeve that has been bothering you, is critical.

If you do decide to build the product, you should take the time to figure out what has already been done elsewhere, and what other companies have done to address the problem you are trying to solve.

7. Product

At the very top of the reliability pyramid, balancing on top of all of the other layers is the actual workable product itself.

After spending over ten years honing its launch process, Google identified several key criteria that characterize a good launch process. They define a good launch process as lightweight, robust, thorough, scalable, and adaptable.

Given that some of these requirements are in obvious conflict, balancing them against one another requires continuous work. Therefore, organizations are encouraged to emphasize simplicity, use a high-touch approach that enables experienced engineers to customize the process to suit each launch, and fast common paths that allow engineers to provide a simplified launch process for classes that always follow a common pattern.